How Islamic Influence Shaped Medieval Europe’s Architecture

Islamic craftsmanship played a key role in shaping some of Europe’s most iconic medieval structures.

EUROPE (MNTV) — Research indicates that Islamic craftsmanship was instrumental in the development of Europe’s most famous religious buildings, including Mont Saint-Michel, Durham Cathedral, the Basilica of Santiago de Compostela, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and Sicily’s Cappella Palatina.

In her book Islamesque, author Diana Darke argues that medieval European architecture was significantly influenced by the advanced knowledge and skills of Muslim artisans.

Darke suggests replacing the term “Romanesque” with “Islamesque” to better reflect the profound contributions made by Islamic craftsmanship, as reported by Religion Unplugged.

Her research, which spans sites in Europe, North Africa, Turkey, and the Middle East, highlights the rich history of cultural exchanges that helped shape religion, art, and society during the medieval period.

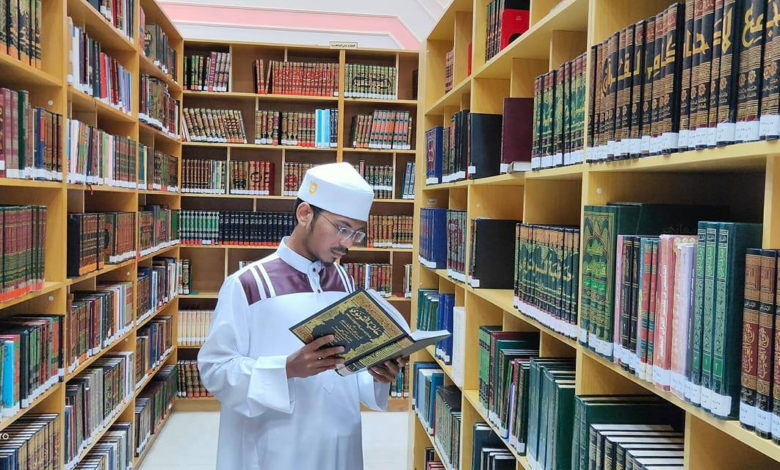

Darke points out that Muslim cities of the time were technologically advanced, boasting systems like running water, efficient drainage, libraries, and public services, which were far ahead of their European counterparts.

Islamic artisans were experts in engineering, mathematics, and ornamental design—skills that were crucial in transforming European architecture.

“All the innovations attributed to Romanesque—vaulting, intricate framing, interlace patterns, and sculptural motifs—can be traced back to the East,” Darke writes.

She further highlights that Christianity itself originated in the East, in a region that was influenced by various cultures, including Islamic ones.

This blending of traditions is particularly evident in Sicily’s Cappella Palatina, where Norman King Roger II employed Byzantine mosaicists and Muslim craftsmen from Cairo. The ceiling features stunning wooden carvings with floral patterns, eight-pointed stars, and lively depictions of music and dance. Roger’s coronation robes were inscribed with Arabic text and a Hijra date.

Similar examples of cultural fusion can be found across Europe. Wells Cathedral in England displays Arabic numerals on its sculptures, while the ceiling of Peterborough Cathedral incorporates Islamic design elements.

In France, anti-Pope Benedict XIII hired Muslim artisans to build churches, while Christian craftsmen contributed to mosaics at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.

These cultural exchanges were facilitated by trade routes and Europe’s growing wealth during the Middle Ages, enabling churches and cathedrals to hire the most innovative craftsmen. Techniques were shared in both directions, with Muslim and Christian artisans collaborating on significant projects.

Darke also notes the lasting impact of these influences. For example, Muslim craftsmen from Atelier de la Grande Oye were involved in the restoration of Notre-Dame de Paris. Founder Paul Muhsin Zahnd described their work as a spiritual journey, combining their faith and artistry to celebrate beauty and creativity.

Darke’s findings challenge traditional historical narratives, revealing the profound influence of Muslim-Christian collaboration on Europe’s architectural heritage.